‘Ein Freund, ein guter Freund …’

Above: The Comedian Harmonists

Ein Freund, ein guter Freund,

Das ist das Beste, was es gibt auf der Welt

Ein Freund bleibt immer Freund,

Und wenn die ganze Welt zusammenfällt

Click on the picture above to hear a recording of a well-known German song about friendship. First written by Robert Gilbert (words) and Werner Heymann (music) in 1930 for the early musical film Die Drei von der Tankstelle/The Three from the Filling Station (1930), it’s been rerecorded by many German artists, including this acapella version by the Comedian Harmonists.

Friedrich Schiller’s An die Freude/Ode to Joy is another very famous poem about friendship, later set to music by Beethoven. It expresses powerful ideas about the common humanity of all mankind, based on the Enlightenment philosophy of the time. According the poem, shared experience (especially of nature) unites people all over the world, including those separated by different languages, traditions and social classes. At the time, this was quite a revolutionary idea! It’s clear why the song was chosen as the Anthem of Europe in 1972. Click here to listen to a version sung by London's Philharmonia Chorus, and read the lyrics in German and English.

Double acts – and odd couples!

The ‘double-act’ or Komikerduo is a form of artistic partnership with its origins in comic theatre. Double-act often take the form of unlikely friends or contrasting types: two people with very different comic styles or physiques who play with and against each other for laughs. Two Austrian actors, Rudolf Walter and Josef Holub, are credited with appearing as the first Komikerduo on the big screen as Cocl & Seff – a format which influenced Laurel and Hardy, among others.

Above: Karl Valentin und Liesl Karlstadt in Mysterien eines Frisiersalons (1932)

The long-running artistic partnership between Karl Valentin und Liesl Karlstadt began on the stage in cabaret performances from 1911, and later transferred into film. Their first short film Mysterien eines Frisiersalons (1932) was directed by Erich Engel and Bertolt Brecht. Click the picture above to watch it on YouTube.

Keeping in touch

Until relatively recently, friends who lived in different places kept in touch by letter or (later) telephone. Sometimes, their private correspondence has been published so that everyone can read it and learn about their friendship: famous examples of this are the correspondence (‘Briefwechsel’ in German) between the writers Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) and Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805) or that between poets Ingeborg Bachmann (1926-1973) and Paul Celan (1920-1970).

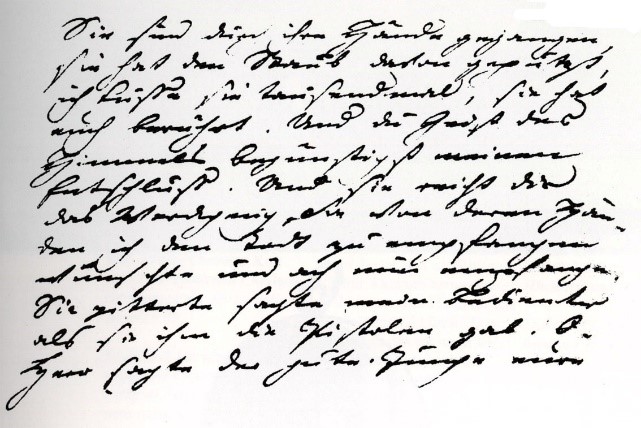

Above: An extract from the manuscript of Goethe's Leiden des jungen Werthers, 1774/8

In the eighteenth century, many authors wrote fictional letters as a way of telling a story. This form of writing is known as an ‘epistolary novel’: Goethe’s bestseller Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (The Sorrows of Young Werther, 1774/8) is told in this way, as a series of letters from the character of Werther to his friend Wilhelm. Women writers such as Sophie von la Roche and Bettina von Arnim also used this style of storytelling.

Read many more famous and fascinating private letters, between friends and strangers, on the blog Letters of Note.

Facebook ‘friends’?

The digital age has transformed the way we make friends and keep in touch. Instead of laborious letter writing, most people now send emails and instant messages – peppered with their favourite emoji rather than written in beautiful longhand! Some people mourn the lost art of letter-writing, but others celebrate how much easier it is to find new friends, reconnect with lost ones or stay in contact with people from all over the world.

What do you think? Are you really ‘friends’ with all of your Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat or Instgram contacts – or has social media changed our definition of the word, for better or worse?

The language of friendship

The clearest marker of the beginning of a friendly relationship in German is moving from using the formal ‘Sie’ to the informal ‘du’ – usually after one party has suggested this to the other, a process known as ‘offering the ‘du’ or ‘das Du anbieten’. ‘Siezen’ and ‘duzen’ can seem like a complicated system to English native speakers who are learning to speak German, but many languages use grammatical structures like this to distinguish formal and informal relationships.

The internet age has offered a new vocabulary of friendship in both English and German: ‘to friend’ somebody, as on a social media site, becomes ‘adden’ in German – and the new words ‘defriend’ or ‘entfreunden’ reflect how much easier that process is in the modern world.

Language teachers have long warned their pupils about false friends or ‘falsche Freunde’ – what linguists call ‘false cognates’. These are words which sound alike but have totally different meanings. You’ve probably fallen foul of a few yourself. For example, few German speakers would be pleased to receive ‘ein Gift’! Here's a list of some with their meanings in English and German.